Understanding culture

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures have adapted dramatically to accommodate all that has been introduced into Australia since 1788.

You sometimes hear people say that ‘real’ Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures no longer exist because we no longer live like our ancestors, using traditional hunting implements and the like. This makes about as much sense as saying that English culture no longer exists because English people don’t live as they did before the industrial revolution.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures have adapted dramatically to accommodate all that has been introduced into Australia since 1788. First Australians have proved to be rich and resilient. It is a strong part of who we are and it is a strong part of the Australian identity.

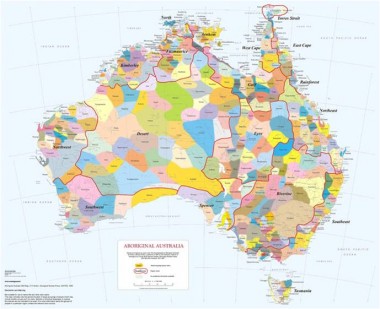

It is important for all Australians to understand the essential features of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures, including our special connection to the land and our commitment to family and community—so we can walk on this land together as friends and equals, so you can share our pride.

Understanding and respecting our cultures also gives you a better sense of the impact on our communities when life-sustaining structures are ignored or broken, as they have been and continue to be.

Elements of traditional Indigenous culture, with spirit at the centre, creating deep connection with land and sea, sustained by a range of human practices. ©Kim Bridge